The Science (and Seduction) of Product Storytelling

How to earn attention without losing trust. Part 2 of 3.

“Water, water, every where,

And all the boards did shrink;

Water, water, every where,

Not any drop to drink.”

So reads the Rime of the Ancient Mariner, the story of the sailor returned from sea, who corners a wedding guest and tells a tale he cannot stop telling – and the wedding guest cannot stop hearing. While there may be something of the supernatural in the Mariner’s “glittering eye”, there may also be something scientific happening here.

So, why do some stories hold the listener so transfixed?

Welcome to the second in a three-part series on Product Storytelling for the Climate: a practical framework for early-stage founders in climate and nature tech. This edition explores the science behind storytelling and the ethical stakes when you use that to drive action.

But first: a warning.

(And no, it’s not a reminder to not be that startup Mariner at a wedding...)

The dark side of storytelling

In 1979, Joan Didion famously wrote: “We tell ourselves stories in order to live”.

This line has become interchangeable with our hardwiring for stories in life, leadership and love: the way that our language and memory hold ourselves and each other together.

But Didion’s next few lines are often forgotten:

We look for the sermon in the suicide, for the social or moral lesson in the murder of five. We interpret what we see, select the most workable of the multiple choices. We live entirely, especially if we are writers, by the imposition of a narrative line upon disparate images.

In other words, storytelling is not just instinct but also compulsion. We crave order. We impose meaning. We freeze the shifting, uncertain nature of life into shapes we can survive.

In climate tech, this tension is especially sharp.

On the one hand, we must tell better stories that move people to act. On the other, we risk massaging reality into narratives that are too neat, too feel-good, too commercially convenient.

Last week, I was sorting through a box of old children’s books for a reading charity and noticed a headline printed on the back cover of a book for a Stage 1 reader: “70 years of visual storytelling”. It struck me as odd – not because it was wrong, but because ‘storytelling’ has become so commodified, it’s almost lost its meaning. Work events, conferences, TED talks, and articles (yep, like this one) arguably talk about storytelling more than the stories themselves.

In an essay for GriffithReview 44 (republished in the Inside Story in 2014) writer Maria Tumarkin recalls an environmental journalist speaking at an ideas festival in Sydney: “If the public is not with us yet, it means that we haven’t told the story of global warming well enough.”

Tumarkin critiques this idea – the seductive belief that if only we spin the narrative wider, thicker, stickier, the public will inevitably get caught. She writes:

“You work on your story arc, you describe a moving personal journey, you take your audience on that journey with you, you land the story well, with a bang, with a message (but don’t make it too heavy-handed) and all the while you skilfully steer your audience away from despair towards a sense of empowerment.”

This was almost exactly the advice I’d planned to write here, line by line. The danger Tumakin points out is the “nauseous, seductive” quality to polished storytelling. In climate communications in particular, there’s a risk of comforting people into inaction, or turning crisis into commodity.

Rather, Tumakin – echoing journalist Katherine Boo – points out that stories must be “earned facts”, not manipulated character arcs.

And yet their importance is undeniable. Just think of the hit show Adolescence, which started conversations around the online influences that inform masculinity in classrooms and homes across the UK. Or Prima Facie: the one-woman play with Jodie Comer exposing the flaws of the criminal justice system to adequately address sexual assault cases.

So, how can you still earn your stories without getting that icky feeling?

Let’s turn to the science.

The science of storytelling

If we go back to the Ancient Mariner and ask why the “Wedding-Guest stood still, [listening] like a three years’ child: / the Mariner hath his will”, neuroscience offers part of the answer.

Mirror neurons

You’ve probably heard that when we hear stories, the neurons in our brain fire in the same patterns as the speaker’s, a process known as neural coupling.

According to highly influential work by Greg J. Stephens, Lauren J. Silbert, and Uri Hasson, these processes light up many different areas of the brain, and can induce a shared contextual model. Everything is engaged, across the motor and sensory cortices, as well as the frontal cortex – nurturing and solidifying the network with the anticipation of the story’s resolution, and that all-important hit of dopamine.

Emotional response

This release of dopamine makes it easier to remember stories with greater accuracy, while the amygdala, the brains’s emotional centre, is said to flag these memories for long-term storage.

For instance, if you think back to your earliest memories of childhood, there’s a good chance you remember the smells, texture, sound, weather, and lighting decades later. This is the same technique that TED Talks use to structure their stories – opening with sensory, emotional hooks to make their stories memorable.

Narrative transportation

When listening to a particularly good and emotionally-charged story, we also may experience what’s called narrative transportation (Green & Brock, 2000), mentally and emotionally stepping into the story world and imagining ourselves in the same situation. In marketing, this is what may turn a passive consumer into an active participant.

An example of this would be the travel ads in the London Underground, transporting sardine-can commuters into the sparkling waters of the Mediterranean.

When someone scrolls through your website, how can they see themselves living the future you’re building?

Social proof and relatability

When we see someone like us navigating a challenge, it validates our own emotions and behaviours.

Highlighting stories from employees, customers, and other industry players build trust and drive engagement, with campaigns like Movember seeing a 20% engagement boost after encouraging personal storytelling (Smith et at al., 2017).

For climate and nature tech startups, this neurological wiring offers an enormous opportunity and responsibility.

You’re not just marketing a product but inviting your audience into your ‘world’: a world that must feel real enough to believe in, important enough to matter, and human enough to connect to.

Subscribed

Key concepts for product storytelling

The hero’s journey:

To Tumakin’s point, compelling product stories typically mirror the classic arc: a character (your customer) faces a challenge, encounters a guide (your product), and overcomes adversity to find transformation. Keep it simple.

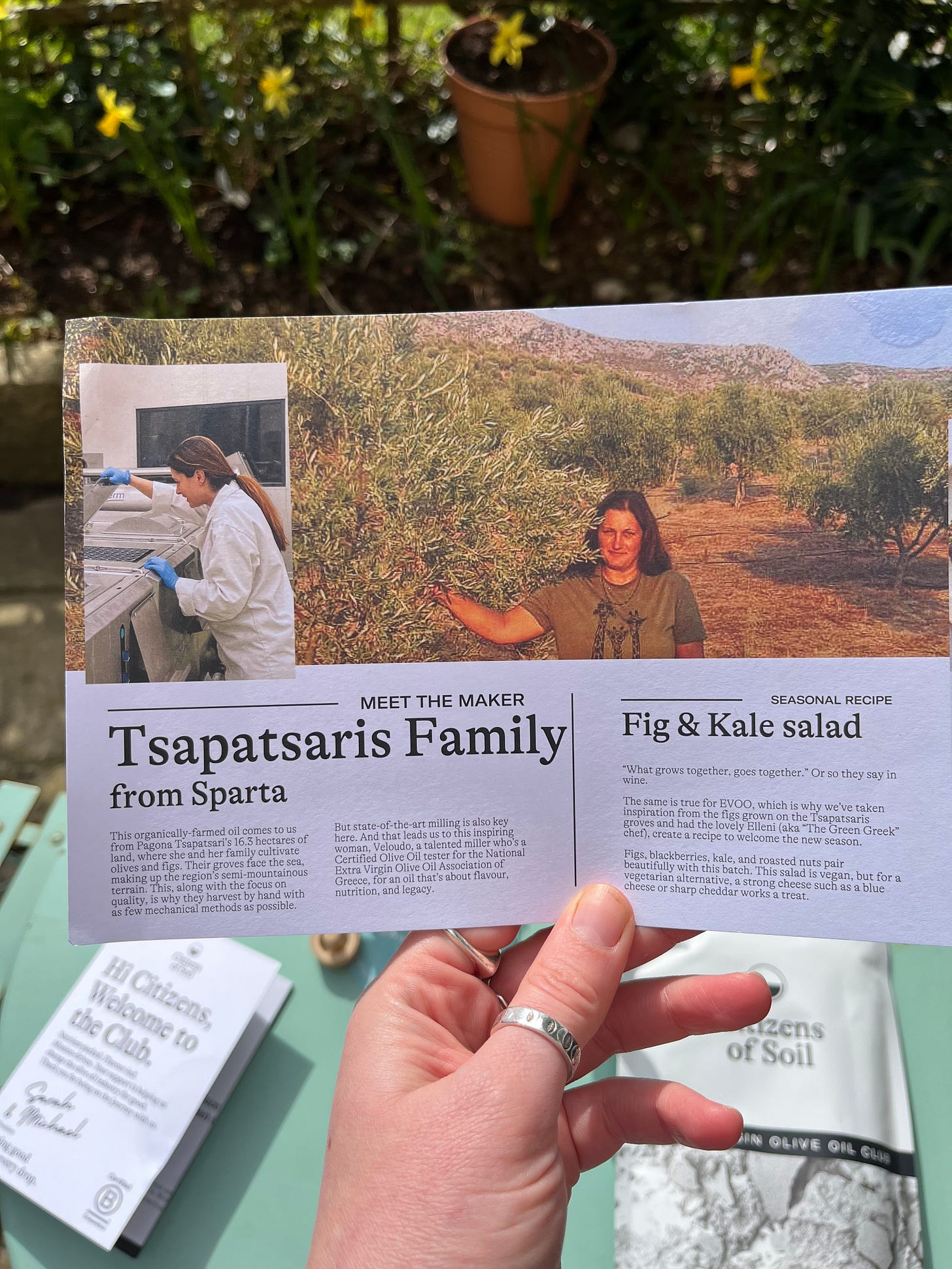

Example: For example, Citizens of Soil markets its traceable, small-batch, regenerative olive oils by positioning the customer as part of a global movement toward restoring soil health, honouring traditional practices, and rebuilding broken relationships between land and table.

It aligns with the Hero’s Journey to inspire and motivate as well as steward for generations to come.

Archetypes:

Christopher Booker argues that there are no new stories, only old archetypes dressed in new clothes. Understanding Carl Jung’s archetypes (like the Sage, the Explorer, the Caregiver, the Rebel) helps your audience instinctively connect and help define your brand identity.

Example: For instance, Patagonia uses the ‘Rebel’ and the ‘Caregiver’ archetype in its campaigns, focusing on bold activism alongside deep responsibility towards the natural world.

Conflict and resolution

Without stakes, there’s no story. Without struggle, there’s no trust. Don’t flatten complexity or sand down the sharp edges of ecological, political, or technological tensions to make your product look perfect; instead, show how it meets real-world tension and real, urgent tensions.

Example: Take many of the physical climate risk platforms’ marketing. They will typically highlight the frustration with existing technology and outdated, opaque carbon accounting then present their products as the solution for rigour, speed, and transparency.

They do not shy away from the uncomfortable truth that most emissions reporting is self-reported and unreliable. Instead, their story confronts the broken system and offers radical transparency as the way forward.

Additional storytelling concepts

Multimedia & visual storytelling

According to this 2014 study, our brain can process an image in as little as 13 milliseconds, which is why great stories show rather than tell. Incorporating data-driven charts, illustration, and visuals will make your narrative stronger and stickier.

What’s more, stories are even more powerful when they unfold across formats: text, video, podcast, event. For instance, a climate startup building a ‘franchise’ around regenerative farming could create mini-documentaries, founder podcasts, and on-site storytelling hubs or micro-sites.

Example: Oxygen Conservation are doing this brilliantly with their Shoot Room Sessions, a human-led approach centred around conversations in conservation.

Personalisation

Spotify’s “Wrapped” campaign is iconic because it turns customer data into a personal narrative that people can see themselves in. Research by the NeuroLeadership Institute (NLI) found that the most-remembered stories leave the listener with deeper insights, defined in this context as the moment an individual goes from no-solution to solution – otherwise, the ‘Aha!"‘ moment.

Example: In sales calls, you can structure the discovery and product demo calls around story frameworks by prioritising a two-way conversation – one that raises a sense of primary relatedness, builds connections, and focuses on strengthening the relationship.

Cultural storytelling

Cultural storytelling connects the product’s narrative to broader cultural themes and values, making it more relevant and accessible to your target audience.

Example: Bodyform’s “Never Just a Period” campaign rooted brand messaging in broader cultural narratives, challenging not just the fact that most period ads will show menstrual blood as blue but the wider lack of education and research into women’s health.

Successful examples of product storytelling in climate

Patagonia

While not a pure “climate tech” company, Patagonia remains the gold standard for storytelling in the climate movement. Through its corporate activism (Earth is now our own shareholder) and campaigns like Worn Wear, Patagonia shows how consistent, values-driven storytelling can forge unparallelled trust and loyalty.

Charity: Clean Cooking Alliance

Clean Cooking Alliance (CCA) uses storytelling to highlight the impact of clean cooking on communities. By sharing detailed stories of individuals benefitting from their work alongside publishing guiding principles for carbon project developers, they engage donors and drive contributions. Their storytelling approach has helped raise over $25 million, engaging millions of supporters worldwide.

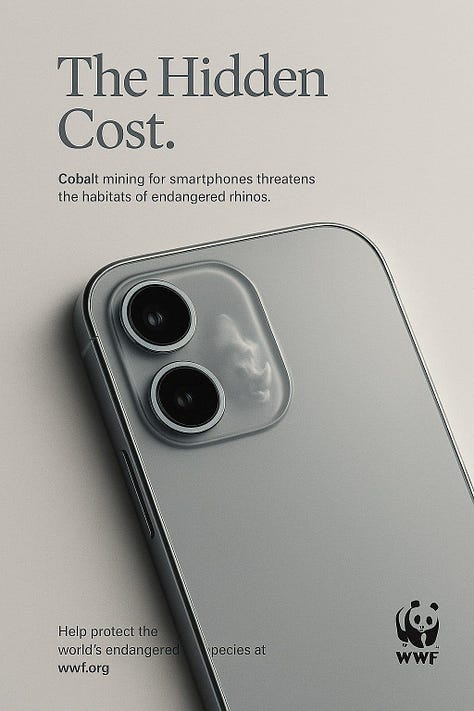

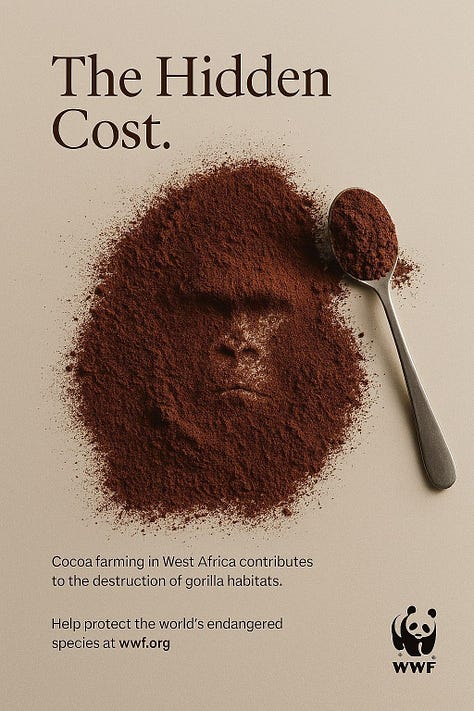

WWF

WWF’s recent Hidden Cost Campaign led by Nikolaj Lykke Viborg, Earthmark, Jack Linnet and team spotlighted the invisible cost of everyday products like cocoa, coffee, avocado, rice, and iPhones on biodiversity, water, and carbon.

While the campaign has come under some fire for its use of AI and the associated environmental impact, its use of imagery to tell a story in one narrative beat is extraordinary.

Bold Bean Co.

It’s no secret that I’m obsessed with Bold Bean Co. Just this morning, I hovered over the bean section and wondered about what recipe to make with the Queen Butter Beans (described as Big. Velvety. Tender) or the new collab with Ottolenghi in the shape of Queen Black Chickpeas.

Whether it’s the product copy, quality, or the CEO and Founder, Amelia Christie-Miller’s personal posts on LinkedIn, Bold Bean Co’s brand feels like a masterclass in founder-led branding.

Citizens of Soil

Now, this one’s a little biased (I use their olive oil subscription with Nipotina) but Citizens of Soil immerses you in a world of sun-parched olive groves, wind-burnt coastlines, and family trattorias. It is a love-letter to women olive oil producers who take exquisite care of the land and the soil, plus make delicious oils to boot.

Regeneration goes hand-in-hand with taste, aspiration, and product quality.

The welcome pack for Citizens of Soil in March (2025).

The process of product storytelling, then, is to try your damn hardest not to over-edit or polish the story in a way that you lose the very thing that makes it interesting.

Instead, stay as close as you can to the rough grain of reality, even when that story is messy and changing all the time. You need to hold the concept of simplicity and memorability in one hand, while balancing it with a deep respect for the end customer with the other.

I’ll end with the eternal, salt-crusted words of Coleridge:

“I do not deny that it is helpful sometimes to contemplate in the mind, as on a tablet, the image of a greater and better world, lest the intellect, habituated to the petty things of daily life, narrow itself and sink wholly into trivial thoughts. But at the same time we must be watchful for the truth and keep a sense of proportion, so that we may distinguish the certain from the uncertain, day from night.” – Samuel Taylor Coleridge

Ultimately, in climate product storytelling, the work is to earn the stories – by staying as close as you can to the truth, then beginning (and ending) with a deep and nuanced understanding of your customer.

I’d love to know, have you felt the storytelling ‘ick’ too lately?

About me + Cantadora

If you're new here, welcome! I'm Emma – a fractional climate tech marketer and part-time pasta nonna in training. Cantadora gives climate and nature tech startups the product marketing and marketing content foundations they need to clarify their value proposition, build engaged communities, and create an inbound lead engine.

Thank you so much for reading this Fourth Edition of Field Notes – a guidebook for founders who want to tell better stories.

In the final part, we’ll be turning the ideas from this and Part 1 into a repeatable, buildable storytelling system – covering the story architecture basics and how to build a story bank.

Until then, thank you for being here.

– Emma from Cantadora

Further reading